The story of Venus: NASA’s Lori Glaze talks about the selection of the two new NASA missions to Venus

NASA have selected two new Venus missions to be launched at the end of the decade. Cosmos caught up with NASA’s Lori Glaze to ask why the time is now right to journey to Venus.

“It was a big and happy surprise, to both me and the whole planetary science community,” describes Dr Lori Glaze, Director of the Planetary Science Division at NASA. “I think many in our field recognised it was well past time for NASA to return to Venus, but to see both the Venus Discovery concepts selected together was pretty amazing.”

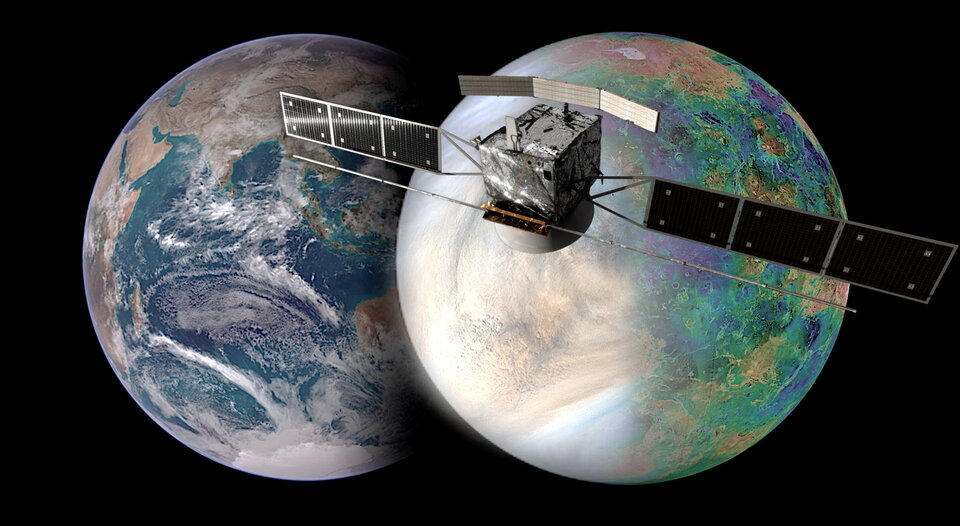

In June this year, NASA announced the selection of two new missions for the agency’s Discovery Program. In an unexpected twist, both the chosen spacecraft will be heading for our neighbouring planet of Venus.

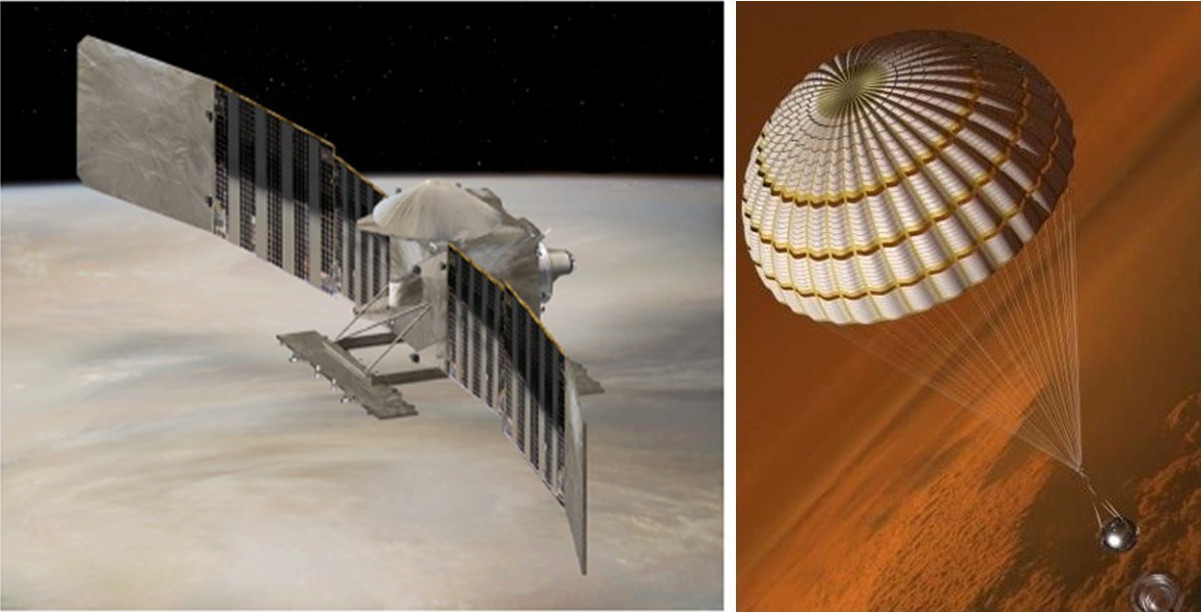

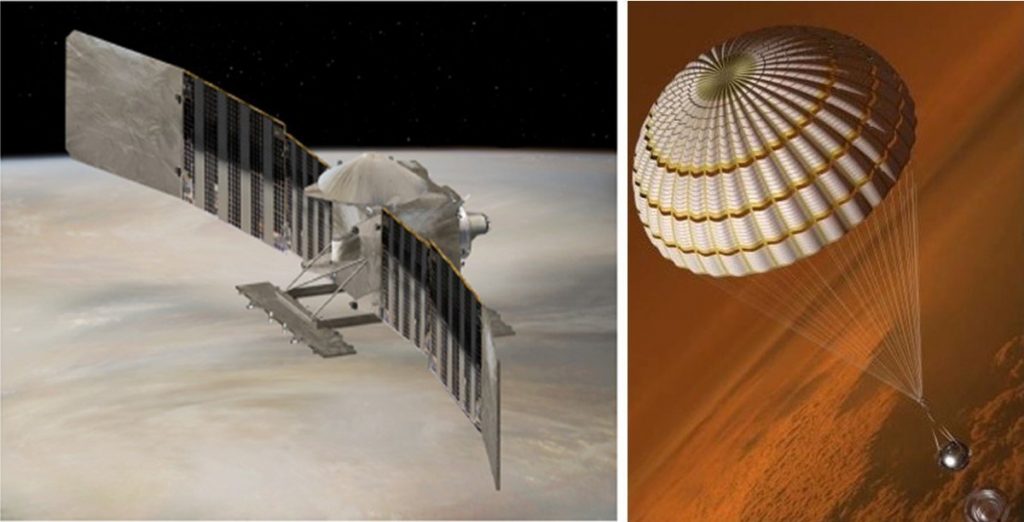

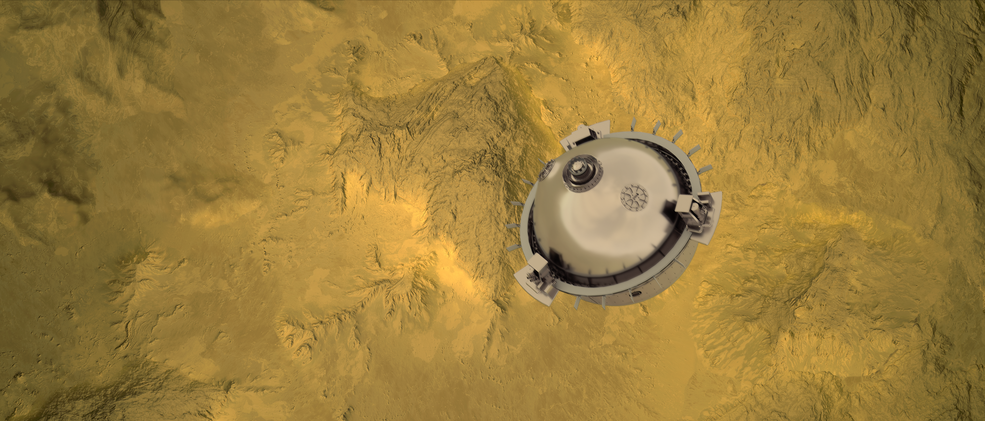

The DAVINCI mission is focussed on the atmospheric profile of Venus from cloud top to surface. Once at the planet, DAVINCI will deploy a probe that will take measurements of the temperature, pressure and composition of the planet’s atmosphere as it descends towards the surface. The probe will also capture high resolution images of the ground before landing, although the crushing pressure and temperatures mean that the craft is not expect to have a lifetime on the surface itself.

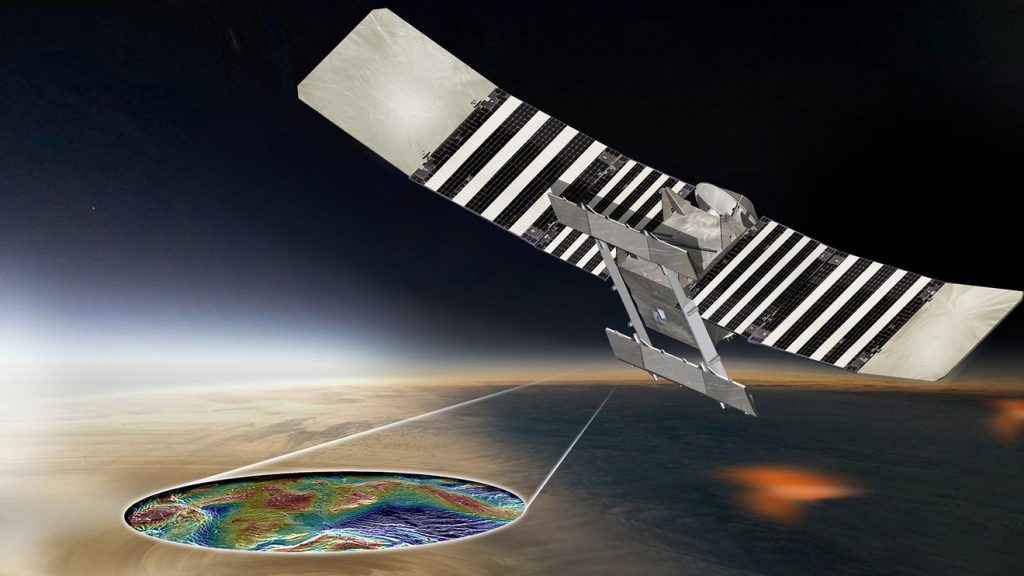

The second mission is VERITAS, which is an orbiter focussed on the structure of Venus’s surface and interior. VERITAS will look through the clouds that envelop the planet to create three-dimensional maps the Venusian surface, identifying any signs of geological activity such as volcanos or mobility similar to the Earth’s tectonics.

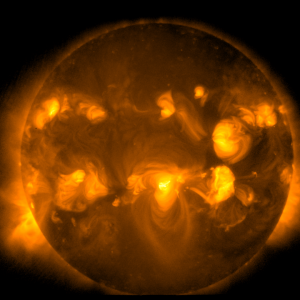

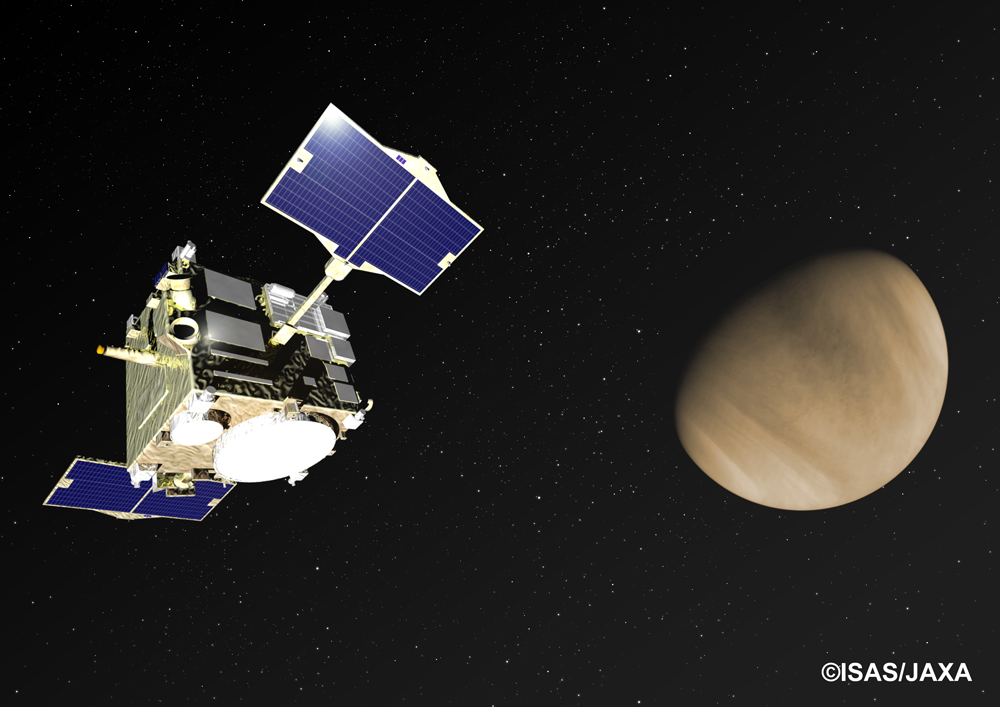

Data from both of these missions will complement results from JAXA’s Akatsuki climate orbiter, which has been studying the extreme weather of the upper cloud deck of Venus since December 2015.

NASA began the Discovery Program in 1992 and has to date launched 12 missions in this category. In total, the NASA Planetary Science Division has four classes for space missions, covering a range of budget and scope. Discovery sits between the smallest mission class, SIMPLEx (Small Innovative Missions for Planetary Exploration) that generally involve spacecraft a little larger than CubeSats, and the larger New Frontiers and Flagship categories.

“With Discovery, we give scientists a chance to dig deep into their imaginations and find new ways to unlock the mysteries of our Solar System,” explains Glaze. “The goal is to achieve outstanding results by launching more smaller missions that use fewer resources and involve shorter development rounds.”

It is the curiosity of individual mission teams that determines the destination of the Discovery Missions, while the targets for the two larger mission classes are driven by community-wide recommendations laid out in decadal surveys, or NASA’s strategic goals.

Glaze notes that while it was initially surprising to select two Discovery Venus missions, it was swiftly realised that the two spacecraft together would have an opportunity to attain science results greater than the sum of their parts. It is a concept that resonants strongly with both NASA and JAXA, as the two space agencies have an agreement to exchange samples returned by their respective asteroid missions, OSIRIS-REx and Hayabusa2. In order to unravel complex questions such as how a planet evolved, it is essential to have more than one data set. Parallel missions provide information on different attributes, and also confirm any discovery is not anomalous.

DAVINCI and VERITAS will be the first time NASA has sent a mission to Venus in thirty years. The last NASA mission was the Magellan orbiter in the 1990s, which still provides our best surface data of the planet to date. As a Venus scientist herself, Glaze has been involved in many mission concepts to return to our neighbour over the decades that were ultimately not selected. So why is now the right moment to return to Venus?

“Space exploration—at its most compelling—is about stories,” Glaze notes. “It’s about the major driving questions that we seek to answer by visiting other worlds our Solar System has to offer.”

The steady exploration of Mars by NASA, Glaze explains, has been about the search for life on the red planet, be it current or past. It is a topic that grips us all, regardless of scientific background. The interest in Venus is driven by the coordinated reasons put forwarded by the scientific community that paint the planet’s own compelling tale. The story of Venus is the story of Earth and the search for understand habitability.

“In terms of size, mass, and distance from the Sun, Venus is basically the Earth’s twin,” Glaze explains. “Yet conditions on the two planets today could not be more different. As we seek to understand the history and future of our own planet, such as the effects of climate change, studying Venus and unlocking new findings about its evolution can help us understand our own home.”

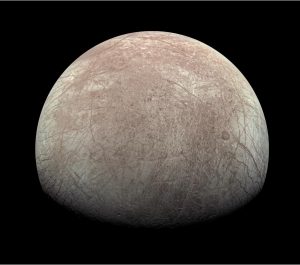

The potential importance of these findings are not only limited to the Earth. Outside our Solar System, there has been an explosion of discoveries of planets orbiting other stars. As smaller worlds with similar sizes to the Earth and Venus have been discovered, questions have turned to the chances of these supporting life.

“The more we learn about the characteristics of the planets in our backyard, the more we will be able to discern about distant exoplanet worlds,” points out Glaze.

Indeed, Venus has even caused us to question what constitutes habitability, as a potential detection of phosphine in the Venusian atmosphere triggered a discussion about whether this could be produced by life in the clouds.

“The huge level of scientific debate and interest the uncertain finding generated, exemplified how hungry scientists are to go back to Venus and learn more of its secrets,” concludes Glaze.

While it is difficult to guess what will be the most important measurements captured by DAVINCI and VERITAS, Glaze offers a few teasers.

“For DAVINCI, I’m excited to see the new precise measurements of noble gases, and other species, in the planet’s atmosphere,” she says of the descending probe mission. “So that we can understand why Venus is in a ‘runaway hothouse’ situation, unlike the Earth.”

Noble gases are extremely unreactive, so their abundances should not have altered significantly since the planet was first formed. Comparing the quantity of noble gasses on the Earth and Venus will therefore reveal if the two planets formed from similar starting conditions, or if perhaps Venus was doomed from birth.

“DAVINCI will also be getting the first high-resolution pictures of Venus’s tessera, which are thought to be equivalent to Earth’s continents,” continues Glaze. “In concert with the global high-resolution topography, synthetic aperture radar images and infrared measurements from VERITAS, we will start to really get a handle on the nature and evolution of Venus’ lithosphere, and may even find that the planet is still geologically and tectonically active today.”

Despite being the same size as Earth, Venus appears geologically sluggish. There is scant evidence for processes such as volcanic activity or a mobile surface (lithosphere) layer. On Earth, this planet activity has been essential for maintaining conditions suitable for life. Did Venus never develop an active geological system? Or did the planet once rumble similar to the Earth but fade out? Is there any activity left today that could reveal clues of how such processes develop or fail?

Tesserae are thought to be the oldest part of the surface of Venus and the high resolution images captured by the descending DAVINCI could reveal structures that indicate these were once continents surrounded by sea. Orbiting above the planet, VERITAS will take radar images to create three dimensional maps of the entire Venusian globe. Together with measuring the infrared emitted from rocks below, VERITAS can seek out signs of crustal movement or volcanic hot spots. Combining the data sets will provide a picture of the planet’s past and current situation.

The compelling tale of Venus has charmed more than the NASA Discovery selection teams. One week after NASA announced the selection of DAVINCI and VERITAS, ESA revealed that Europe would also return to Venus with their new mission, EnVision. Could this indicate a long-term focus on Venus across the globe?

“It is my absolute desire for Venus to continue being a focus beyond these missions,” says Glaze firmly. “It’s important to remember that selecting and investing in missions is about the science, but just as importantly it’s about the people. It’s about the engineers and scientists who will develop the technology, will build the spacecraft, will operate the missions, and who will analyze and interpret the data for many years—or decades—after the missions have ended.”

Glaze hopes the missions will act as a focus to build the Venus community for the next generation and beyond. Moreover, the international interest in understanding the story of Venus provides an opportunity to create a truly global collaboration that is packed with ideas.

“By having Venus missions from both NASA and ESA (as well as NASA/ESA-provided instruments on the other agency’s missions), and the ongoing JAXA Akatsuki mission, we have the chance to create an international, diverse, and sustainable community who will continue to drive the exploration of Venus for many decades,” concludes Glaze.

Further information:

Akatsuki Venus Climate Orbiter website

NASA Discovery selection announcement

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post