Keeping out the Earth: Protecting the asteroid Ryugu sample from contamination

“This wasn’t at JAXA, right?!”

The one line email was sent by the ISAS Deputy Director General Fujimoto Masaki to the Astromaterials Science Research Group who manage and analyse the samples returned from deep space. In the curation facilities on the JAXA Sagamihara Campus, samples collected from asteroid Itokawa by the JAXA Hayabusa mission, asteroid Ryugu by the JAXA Hayabusa2 mission, and asteroid Bennu by the NASA OSIRIS-REx mission are meticulously preserved in airlocked cleanrooms. Unlike meteorites which fall from space to Earth, the importance of the rocks collected by humanity’s three asteroid sample return missions is that they have never been altered by the Earth’s environment.

Underneath the horrified question by Fujimoto was a link to a recent media article:

Japan’s priceless asteroid Ryugu sample got ‘rapidly colonised’ by Earth bacteria

The reply came swiftly from the Astromaterials Science Research Group Manager Usui Tomohiro,

“Yes, it is certain that it is not JAXA curation.”

The media article was based on a journal paper that confirmed this assertion. The contamination had occurred on a single 1 mm grain on loan to a research team in London for scientific study. During the preparation for analysis at the UK laboratory, the sample grain had been exposed to the Earth’s atmosphere. Subsequent examination revealed the presence of filaments whose changing number during observations suggested these to be terrestrial microbes.

But it was not the published conclusions regarding contamination that allowed Usui to respond with such certainty. It was due to procedures put in place to protect the Ryugu sample before the Hayabusa2 spacecraft had even launched.

The race against Earth

On 6 December 2020, a bright light streaked across the night sky above South Australia. Displayed on a screen in the mission control room in Japan, the sight raised a whoop of triumph from the spacecraft operations team. Six years after the launch of the Hayabusa2 spacecraft, the capsule containing the sample collected from asteroid Ryugu was home.

On the ground in the Woomera Prohibited Area with special permission from the Australian Government, the recovery team were moving fast. Once the re-entry capsule touched terrestrial soil, a clock began to tick. Within the 100 kilometre-square region of desert that was the expected landing area, the re-entry capsule needed to be located, recovered, brought back to Japan, and secured inside the controlled environment of the curation facilities at the JAXA Sagamihara Campus within 100 hours. If the clock ran out, the mission failed.

“In order to prevent contamination, sample return missions place strict requirements for the time taken to recover the sample container,” explains Nakazawa Satoru, Project Sub-Manager on the Hayabusa2 Team. “For Hayabusa2, this meant that the container had to be transported to our clean rooms within 100 hours of the return to Earth.”

Secured inside the re-entry capsule, the sample container itself was no regular piece of Tupperware. During sample collection, asteroid material rose through the spacecraft sampler horn and into the sample container. The sample container was closed in the vacuum of space above the asteroid surface, sealing with a metal mechanism that sported an aluminium edge. This hermetic seal had been newly developed at JAXA to close so tightly that even gas would be trapped through the return journey to the Earth’s surface.

“To develop a metal seal that can withstand the impact of returning to Earth, I hit the sample container with a hammer more than 1000 times until my muscles ached!” said Sawada Hirotaka, Hayabusa2 Systems Engineer.

While this prevented the Earth’s environment encroaching on the newly sealed samples, what if Hayabusa2 was already carrying microbial passengers that had hitched a ride from Earth during the spacecraft construction? To prevent this, contamination control had begun before during manufacture.

Launchpad

During construction, any parts of the Hayabusa2 spacecraft that were destined to make direct contact with the asteroid underwent a brutal cleaning. The “full course” cleaning procedure consisted of disinfecting washes in isopropyl alcohol (IPA), a mixture of dichloromethane and methanol, and ultra-pure water in ultrasonic baths, all designed to remove any substance that would suggest this spacecraft had been built on Earth.

When development moved to the assembly and testing of the spacecraft, the sampler horn was constantly purged with pure nitrogen gas, and kept under a positive pressure which pushed any errant particles out of the mechanism.

Yet, all of these steps were still not sufficient to guarantee the complete erasure of contamination.

“The many people moving and working in the spacecraft construction area, as well as the different equipment being used in the spacecraft vicinity, meant that it is not possible to completely eliminate contamination,” explains Sakamoto Kanako, from the Astromaterials Science Research Group.

There therefore needed to be a way to distinguish between the returned asteroid samples, and any rogue substances that had potentially latched on for the round-trip from Earth. Monitoring and cataloging possible Earth freeloaders was done via temperature, humidity and particle counters in the buildings where Hayabusa2 was being constructed. This continued as Hayabusa2 was moved to the Tanegashima Launch Center, where dust in the indoor air, and the materials on the floor and shelves, were collected and evaluated in the three buildings where spacecraft operations were conducted. Near the sampler horn, contamination monitoring coupons that could evaluate both organic and inorganic substances were in position right up until launch.

The results from these tests showed only minute levels of possible contaminates, far below what would be the returned mass of sample. But even so, these potential contaminants were preserved and stored, should a comparison with any findings during the analysis of the Ryugu sample be required.

After the spacecraft rose into the sky on 4 December 2014, soil from the launch pad was also scooped up for additional examination. If anything came back, it would be instantly recognised.

The 100 hour race

0 hours:

On 6 December 2020 at 02:32 JST, a ground antenna that had been set up in the Woomera Prohibited Area detected the radio beacon emitted by the descending re-entry capsule. In a few minutes, the capsule would be on the ground, and the 100 hour race to reach the JAXA curation facilities would begin.

The team had taken no chances on locating the re-entry capsule. Five ground antenna and a helicopter decked out with a receiver were listening for the capsule beacon. Should six years in deep space cause the beacon to fail, four marine radar stations were in position to detect the capsule parachute once it deployed. Should the parachute also fail, observations of the streak of light from the capsule as it plunged through the atmosphere would point to the final resting place on the ground. Finally, drone images would be analysed to spot the capsule after landing.

The estimated landing time was between 02:47 – 02:57 JST.

Time 0.

0 – 5 hours:

At 03:07 JST the re-entry capsule landing area had been estimated from the triangulation of detected beacon signals. Ten minutes later, the helicopter left Woomera and headed towards the identified site.

At 04:47 JST the re-entry capsule was spotted from the helicopter.

At 06:23 JST preparations were underway to collect the capsule. A key question was one of safety. Pyrotechnics had been used to release the parachute, and it was possible not all the explosives had been detonated. Despite the desire to move quickly, caution was required.

At 07:32 JST the collection work was complete, and the re-entry capsule was moved to a clean booth named the “Quick Look Facility” that has been set up in a military facility within the Woomera Prohibited Area.

5 – 11 hours:

At 08:03 JST the helicopter carrying the re-entry capsule arrived at the Quick Look Facility. The re-entry capsule was dissembled to remove the sample container, which was connected to specially prepared gas sampling equipment that had been transported from Japan. Known as the GAs Extraction and Analysis System (GAEA), this equipment was designed to remove any gas that was trapped inside the sample container under vacuum conditions.

Despite the incredibly tight sealant on the sample container, some leakage from of Earth’s atmosphere during re-entry was still anticipated. However, the gas pressure inside the sample container was measured at a mere 1/1000th of the Earth atmosphere, and the chemical abundance differed from terrestrial air. Careful analysis of the different gaseous elements concluded that the sample was a mix of extraterrestrial gas emitted by the Ryugu grains and the Earth’s atmosphere. At the very low pressure inside the sample container, the mass of Earth oxygen or water that could have been absorbed onto the Ryugu grains was estimated at tens of micrograms, or about 0.00001 – 0.0001 of the sample mass. The gas that had an extraterrestrial origin became the first gas sample ever returned from deep space.

“While the Hayabusa mission was a technology demonstration, Hayabusa2 was the first mission to put this into scientific practice,” says Tsuda Yuichi, Project Manager of the Hayabusa2 mission and lead for the Extended Mission, Hayabusa2♯. “The Hayabusa2 team approached the development of the sample collection device, sample storage container, and Earth re-entry capsule with the same spirit: the goal was to return material from asteroid Ryugu without any contamination, without any change, and without any leakage of the Earth’s environment to the sample. Hayabusa2 incorporated many steady and precise technologies that bridge the gap between ‘being able to collect a sample’ and ‘collecting a sample that can lead to rich scientific results’.”

Approximately eleven hours after the re-entry capsule landed, the front and rear heat shields that protected the re-entry capsule during atmospheric descent had also been located and brought to the military facility. The bright light that marked the re-entry capsule’s final decent was due intense heating in the atmosphere which would have reached values of around 3000°C. However, the “Re-entry Environment Measurement Module” (REMM) that was mounted on the capsule confirmed that the shields had done their job well. The sample container never reached temperatures exceeding 65°C, far below that needed to dehydrate the sample.

57 hours:

On 7 December at 22:30 JST, the sample container that was still under vacuum conditions was airlifted on a chartered flight from Woomera airport.

On 8 December at 07:20 JST the aircraft landed at Haneda Airport in Japan.

At 10:31 JST the truck transporting the sample container arrived at the JAXA Sagamihara Campus.

At 11:27 JST the sample container was brought into the JAXA Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center: approximately 57 hours after the re-entry capsule had touched the Earth’s soil.

“Although the team had prepared for a variety of different problems, this recovery was achieved in almost the shortest time possible,” notes Nakazawa.

The clock had stopped with over forty hours remaining.

Not even your mother asked you to clean this well

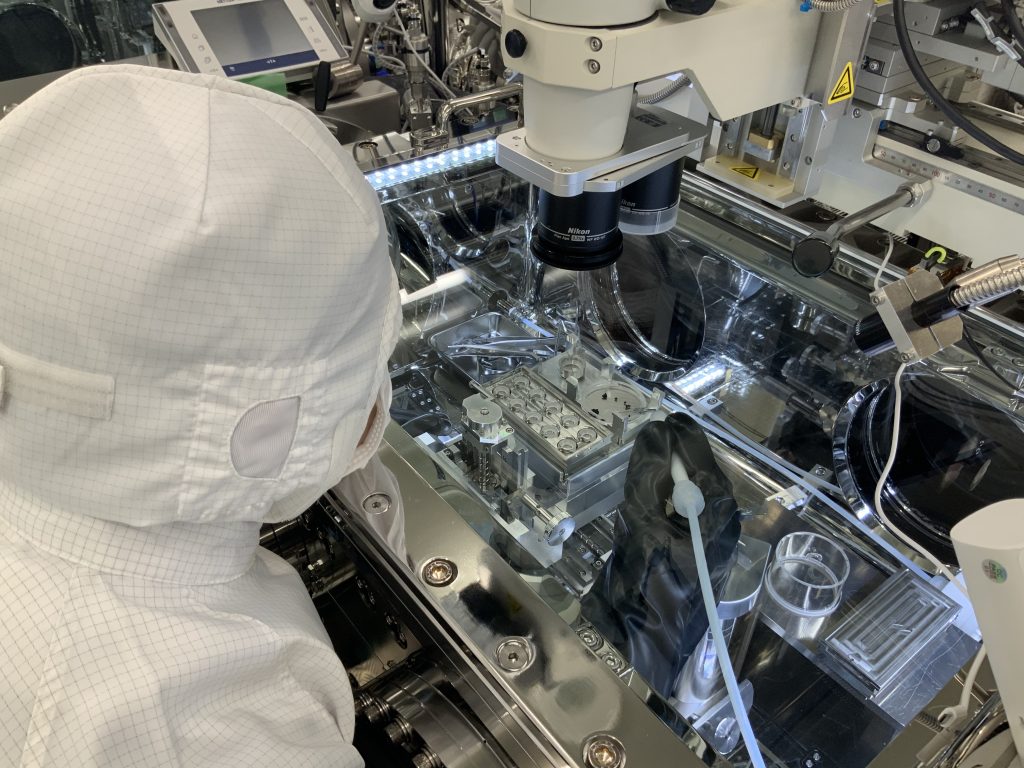

The clean chambers inside the cleanroom of the Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center (ESCuC) are made from stainless steel (SUS304) that has undergone electropolishing and acid-alkaline precision washing on the inner surfaces. Before these clean chambers saw a single grain of the asteroid Ryugu sample, they were evacuated and vacuum-baked at 100°C to remove any atmospheric component that might have been absorbed onto the inner surface.

The clean chambers are in a cleanroom which conforms to a particle cleanliness of IS06, an international classification for the air quality within a controlled environment. An ISO6 designation requires less than 1000 particles (equal or larger than 0.5 microns) per cubic foot, and 180 air changes per hour of HEPA filtered air. Cleanroom personnel must pass through an airlock to enter the room, wear protective suits, and are not allowed to use any substances such as skincare lotions or cosmetics. Regular items such as paper and pencils cannot be used inside the cleanroom, and note taking instead uses tablets or “clean paper” that is specially designed to reduce shedding.

It is in this environment that the sample container was finally opened.

“After the sample container arrived in Japan, unnecessary parts were removed and the exterior was cleaned while maintaining the vacuum environment,” describes Yada Toru from the Astromaterials Science Research Group. “The sample container was then introduced into a clean chamber with a vacuum environment. And in the high vacuum environment of this clean chamber, we opened the sample container.”

Inside the high vacuum environment of this first clean chamber, the sample container was opened to reveal the “sample catcher” that held the asteroid grains.

The sample catcher was transported to an adjacent clean chamber without any break in the vacuum conditions. The lid of the sample catcher was removed and for the first time, the material of asteroid Ryugu was seen directly by human eyes.

The rule book for sample grains

In the vacuum chamber, 2 – 3 millimetre-sized grains were removed from the asteroid sample and stored. The catcher containing all the other grains was then moved to the next adjacent clean chamber. The gate valve between the two chambers was snapped shut, separating the two environments that contained the removed grains and those that remained in the catcher.

The chamber containing the catcher was then purged with high-purity nitrogen gas. Nitrogen is extremely un-reactive, and its use allows sample handling to be performed at atmospheric pressure without the risk of chemical reactions with the sample grains. The impurity concentration of the nitrogen gas is kept below 1 ppm (about 300 ppb), and only containers, tools, and jigs that have been ultrasonically clean with organic solvents and ultra-pure water, as well as either alkali solution or UV ozone cleaning, can be brought into the clean chambers. In these conditions, the sample grains were finally removed from the catcher, separated out, and the initial quantitive description of what Hayabusa2 had retrieved from asteroid Ryugu began.

The initial description consisted of weighing, making observations with an optical microscope, and spectroscopic examination in both visible light and the near-infrared. Spectroscopic observations look at the different wavelengths of light that are reflected by the sample grains and can indicate differences in composition. The sample grains were also stored here for future study.

Handling the samples with the approved clean chamber tools follows a meticulous protocol so that any substances that are generated from wear and tear of the tools do not adhere to the sample surface. Only the sample containers made of sapphire glass, and vacuum tweezers and spatulas touch the Ryugu sample grains directly. The gloves attached to the clean chamber that allow curation researchers to reach inside are made from Viton-coated butyl but never pass over the top surface of the sample during handling. Any particles that originate from these implements also look distinctly different under examination, which allows for easy identification during tests for contamination. Although sedimentation from a few substances from the tools has been identified on the floor of the clean chambers, no significant adhesion of these terrestrial material has been found.

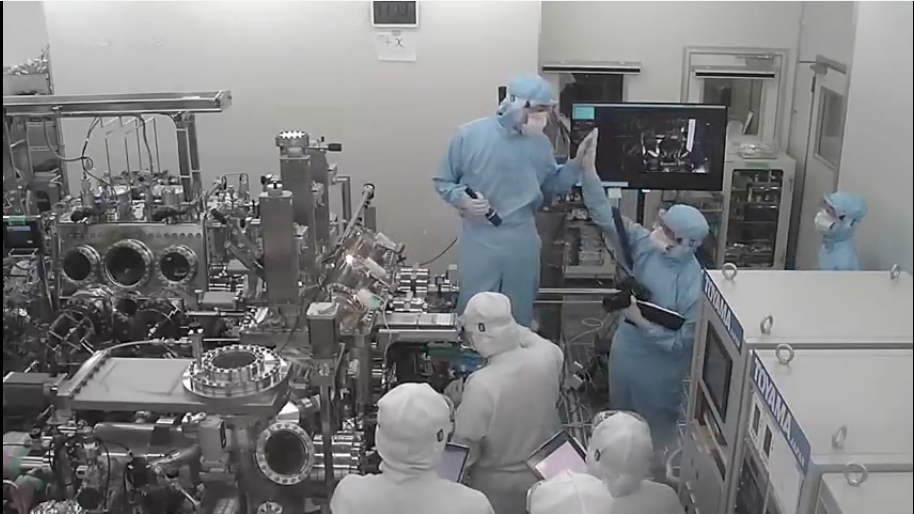

A walk through our curation facilities, by the JAXA Space Exploration Center (JSEC).

An asteroid sample for the global scientific community

The Ryugu Sample Database System can be viewed from anywhere in the world. On this site, the data from the initial description of the Ryugu sample grains can be examined and used to propose a scientific research plan for the asteroid Ryugu sample.

“These research proposals are reviewed by experts from Japan and overseas, taking into consideration not only their scientific value, but also technical aspects such as the handling of the sample and the plans for return to JAXA,” explains Usui. “The review content is then evaluated by a panel independent of the reviewers who have been appointed by JAXA, and potential recipients for sample grains are selected. This list of candidates is finally approved by the Astromaterial Sample Allocation Committee, which is composed of world-class researchers in this field.”

Proposals that are successful after the peer review by domestic and international experts, and discussion by the committee receive an appropriate quantity of the Ryugu sample to conduct their study.

“Through this process, many research proposals have been approved through multiple layers of fair reviews,” adds Usui. “These proposals are based on free and open academic ideas and have already led to a series of wonderful scientific results.”

The allocated sample grains travel to research laboratories around the world in a sealed container known as a Facility-to-Facility Transfer Container (FFTC). The FFTC has undergone the same cleaning procedure as that of the clean chambers and contains a sapphire glass container holding the sample grain that is sealed while in the clean chamber’s nitrogen environment. Only then is the FFTC removed from the clean chamber, where it is further sealed in a gas barrier bag within another nitrogen environment chamber before being either shipped or hand carries to the research institute.

Spotless spot checks

The cleanroom and clean chambers at the JAXA Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center are regularly evaluated for inorganic elements, organic matter, and microorganisms. A microorganism check is conducted 1 – 2 times per year, while surfaces are tested for inorganic and organic elements every 2~3 months, and organics in the atmosphere still more frequently.

“The microbial environment evaluation is performed using many of the same techniques as that used at the NASA Johnson Space Center,” explains Kimura Shunta from the Department of Interdisciplinary Science.

To date, no microbial colonies have been detected in the cleanroom of clean chamber environment when where the Hayabusa2 samples are handled.

Preparing for Phobos

The extreme defenses against Earth contamination at the Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center will be put into practice again as the JAXA Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) mission heads for the moons of our neighbouring red planet. MMX is scheduled to launch in the fiscal year of 2026 and after a detailed examination of the Mars’s two moons, will return to Earth with a sample collected from Phobos in fiscal year 2031.

Roughly two years from launch, and contamination control is already well underway in the cleanrooms where the spacecraft is being assembled. The spacecraft’s sampler systems are constantly purged with pure nitrogen to prevent any intrusion of contaminants and the cleanrooms are also constantly monitored with particle counter and contamination monitoring coupons. The sampling of microorganisms in the cleanrooms has additionally been conducted to accumulate data on anything that might be tempted to hitch a ride and contaminate the spacecraft.

Before launch, the sampler system for the C (corer) sampler and Sample Storage and Transfer Mechanism (SSTM) on the spacecraft will be disassembled for a final time for the full-course precision cleaning using the isopropyl alcohol, dichloromethane and methanol organic solvents, and ultra-pure water. After reassembly, the sampler will be reunited with the spacecraft at the Tanegashima Space Center where the nitrogen purge will continue. MMX will also carry a second pneumatic (P) sampling mechanism developed by NASA, who will perform the decontamination of this instrument. Both C- and P- samplers will continuously be purged with nitrogen.

Environment assessment has already begun at Tanegashima, with a preliminary investigation of the microbial environment (including swabbing the surfaces of equipment and sampling airborne microorganisms) within the cleanroom where any flight model components will be handled.

“As with the Hayabusa2 mission, the MMX team is conducting rigorous contamination control and assessment right from the design and assembly stages of the spacecraft,” says Sugahara Haruna from the Department of Solar System Science. “Environment monitoring will also be conducted at the Tanegashima Launch Site. A preliminary investigation of the microbial environment within the Tanegashima clean room has already been carried out, and preparations for the launch are underway.“

Upon the return of MMX, the samples from Phobos will be curated at the JAXA Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center under similar conditions as those for asteroid Ryugu. As with these clean chambers and cleanroom, the MMX facilities will undergo thorough contamination assessment for inorganic and organic substances, as well as microorganisms.

Viewing a piece of our past

Public exhibits of sample grains from asteroid Ryugu are currently on display in Japan, at the Science Museum in the UK, and Cité de l’espace in France. As with the samples for scientific analysis, the grains on display have been sealed in the same FFTC containers within the clean chambers of the Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center cleanrooms.

Visiting one of these exhibits therefore gives you a genuine glimpse of a piece of our planet’s past: a grain that formed in the earliest days of the Solar System as the Earth itself was just developing, which was carried to modern Earth in a container sealed so tight that it even trapped the first gas sample to be collected from deep space, and was then sealed in pure nitrogen while in a clean chamber.

The Ryugu sample is evidence of our beginnings, and huge care has been taken to ensure this scientific potential is realised.

Further information:

Astromaterials Science Research Group website

News article: “Japan’s priceless asteroid Ryugu sample got ‘rapidly colonised’ by Earth bacteria” from space.com

Journal article: “Rapid colonization of a space-returned Ryugu sample by terrestrial microorganisms” in Meteoritics & Planetary Science

ISAS release: “Regarding the journal paper on microbial contamination found on a grain from asteroid Ryugu” on ISAS website

Journal article: “A curation for uncontaminated Hayabusa2-returned samples in the extraterrestrial curation center of JAXA: from the beginning to present day” in Earth, Planets and Space

Technical report: “Contamination analyses of clean rooms and clean chambers at the Extraterrestrial Sample Curation Center of JAXA in 2021 and 2022” on the JAXA repository

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post