Landing on the Moon: Behind the scenes of the night when SLIM made history

Reported by Elizabeth Tasker (Assoc. Prof.)

Dept. of Solar System Sciences

At 3am on January 20, 2024, the Communication Hall on the JAXA Sagamihara Campus was packed with people. Questions were being taken from the audience of news and media professionals on the SLIM lunar lander that has touched down on the Moon’s surface that night.

A journalist lifted his hand, studying the faces of the JAXA representatives as the microphone was passed to his seat. “Landing was successful…” he began. “…I thought you would look happier?”

Across campus, the corridor outside the mission control room exploded with laughter. The researchers who had worked together on the live broadcast for the Moon landing were gathered around a laptop showing the video stream from the press conference. As tired as everyone was feeling, people began to grin.

January 19 at 11pm: Situation nominal

“みなさんこんばんは。この番組は、小型月着陸実証機SLIMの月着陸運用、および、記者会見のライブ配信となります。”

Seated on a bright orange sofa in front a poster of the SLIM spacecraft, Toriumi Shin greeted the audience who had tuned in to watch the YouTube live stream. In the room next door, I spoke into my microphone for the mirrored channel that had English commentary.

“Good evening, everyone! This is the live broadcast for the lunar landing operations for the Smart Lander for Investigating Moon (SLIM) and the press conference.”

The SLIM lunar lander had launched the previous September, and had taken a long but highly fuel efficient trajectory to the Moon. The spacecraft was now in lunar orbit and preparing for the final descent down to the surface.

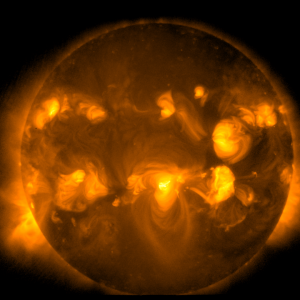

Despite the late hour, ISAS buzzed with activity as researchers from all missions were supporting the live feed. I spotted Sun and Mercury-themed cushions that had snuck onto the sofa beside Toriumi, perhaps positioned so that Toriumi (working on the up-coming SOLAR-C mission) and the live stream co-ordinator Murakami Go (from the BepiColombo Mercury mission) could hug their favourite celestial object if events became too tense.

During the first hour of the live show, Toriumi would chat with the scientists and engineers involved in the SLIM mission. I would provide similar information in English, fervently hoping that everyone would stay roughly to their promised topic.

Then at midnight, the SLIM spacecraft was due to start the final landing descent, and the live broadcast would show the data arriving directly from the spacecraft. Twenty minutes later, the lunar landing would be over.

SLIM mission overview.

“Landing is a one-shot game that cannot be undone,” Kushiki Kenichi, Sub-Project manager for the SLIM Mission, had explained.

While the Moon’s gravity is only 1/6 of that on Earth, it is strong enough that the descent to the lunar surface cannot be stopped once it had begun. Whatever happened after the start of the landing descent sequence, it would end with SLIM on the Moon.

Just down the hallway from myself and Toriumi was the mission control room. About one hour earlier, the SLIM team had been deciding whether to perform the second perilune descending manoeuvre: a pre-landing sequence that would reduce SLIM’s closest approach to the Moon’s surface to just 15km. The operation decision had been “GO”.

In the room where we were broadcasting the English live narration, Frederic Matsuda from JAXA’s proposed LiteBIRD cosmology mission, and Kate Kitagawa from the JAXA Space Education Center sat on my left and right. They were checking the volume level on my microphone and comparing the Japanese and English live broadcasts. Both gave me an encouraging nod.

Situation: nominal.

January 19 at 11:40pm: Twenty minutes until descent

“Space missions are very nerve-wracking because no matter how well you prepare in advance, there are many things you will not know until you actually try,” SLIM Project Member Mori Osamu later reflected.

Even since 2000, the success rate of Moon landings hangs at about 50%. Most recently prior to SLIM, India has succeed in reaching the lunar surface with the Vikram lander, but Russia had failed.

“But that’s precisely why people are interested and are excited to watch,” noted Mori. “We don’t know what will happen.”

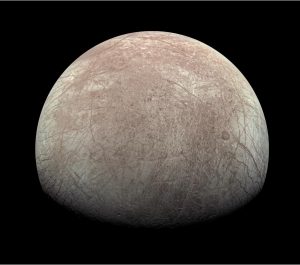

SLIM would be Japan’s first soft-landing on the Moon but more importantly, the team wanted to land the spacecraft with unprecedented precision. While the accuracy of lunar landers is traditionally a few to 10s of kilometres, SLIM was aiming to land within 100m of the target landing site. Close to the Shioli crater, the landing site was also on sloped terrain. A two-step landing was planned to maintain balance, whereby SLIM would first touchdown on its rear leg and tilt forward into a stable position.

Joining Toriumi on the live broadcast, Mori decided to demonstrate the two-step landing using a small model of the SLIM spacecraft in a box of soft sand. This first landing of the evening also had its risks.

“The trick to demonstrating the two-step landing is to give the SLIM model a moderate horizontal velocity,” Mori explained afterwards. “If the horizontal speed is low, the SLIM model will be stuck in the sand and will not fall over (two-step landing failure). If it’s too fast, the two-step landing is over so quickly that it is difficult to understand.”

Mori had previously performed the same demonstration during the launch in September. However, he felt that he had given the model too much speed and the two-step landing had been over too quickly. Mori therefore slowed the model… which stuck upright in the sand.

“I hurriedly tried again and it worked,” Mori said. “But the atmosphere felt a little tense.”

Situation: nominal

January 20 at 0:00 am: Descent

The screen on the live broadcast switched to show a graphical representation of the data being transmitted by the SLIM spacecraft in real time. Known as the “G-Plot” the screen was divided into sections, showing information such as acceleration, angular velocity, remaining propellent, battery capacity, and the trajectory of SLIM compared with the planned path. Exactly the same screen was displayed in the mission control room.

“We went all out to create the greatest possible realism,” explained Fujimoto Masaki, Deputy Director General of ISAS. “This was the screen that you’d actually be looking if you were seated in the control room.”

In the mission control room, Kawano Taro sat in front of an unusual keyboard with just four keys and prepared to move fast. SLIM was aiming to achieve a pinpoint accurate landing by using a technique called “image matching navigation”. As SLIM flew over the lunar surface, the spacecraft would take photographs of the cratered landscape below. Spacecraft software would then identify the craters in the images and match the pattern of depressions to onboard maps of the lunar surface. From this, SLIM would be able to rapidly judge its exact location and autonomously correct its trajectory to reach the target site with unprecedented precision. This was the first time such a scheme had been employed, and Kawano’s job was to have SLIM’s back in the highly unlikely event that the spacecraft made a wrong decision.

As the image matching navigation began, SLIM sent two images to the ground. The first was a photograph snapped by the spacecraft cameras of the lunar surface currently below SLIM. The second was a computer generated image of the lunar surface, based on the coordinates the onboard algorithm had calculated for SLIM’s current position and the lunar maps. If all was progressing smoothly, the two images would match.

In addition to this pair, two independent algorithms running on computers back on Earth performed the same image matching calculation as the onboard computer. They returned two more computer generated images based on the coordinates calculated from the lunar photograph.

Kawano hit the first key on his four-button keyboard. This button flicked the display between the photograph of the lunar surface and one of the computer generated images calculated by an Earth computer. If the pair matched, Kawano hit the second button labelled “OK” and then the final fourth button “send” which reported that result. If the pair did not match, Kawano would rapidly hit the third key labelled “NG” for “not good”, followed by “send”.

“If SLIM has already started to make a course correction based on its own judgement, we wouldn’t be able to fix it in time. So this task had to be done very quickly,” explained Kawano.

In the control room close to Kawano, two other SLIM team members were following the same steps, flipping between the surface photograph and either the onboard computer generated image or the image from the second Earth-based algorithm.

But SLIM didn’t hesitate. The small spacecraft checked its location fourteen times, and correctly adjusted the trajectory. No corrective commands were sent.

SLIM began the final drop towards the lunar surface. On the G-Plot, the spacecraft’s trajectory perfectly aligned with the predicted path. Listening to the team around him, SLIM Project Manager Sakai Shinichiro heard soft “よしっ” (Yes) voiced as SLIM stayed perfectly on target.

There was just over 50m to go.

Situation: nominal

January 20 at 00:20: Landing

Mori Osamu was ready for victory. Describing the features shown on the G-Plot during SLIM’s descent for the live broadcast, he had seen the spacecraft turn to a vertical position and hover, autonomously scanning the ground for any dangerous obstacles to avoid, and then continue to descend. It seemed that everything was going well.

“I thought if the G-Plot switched to show MLM (Moon Landing Mode) and we saw the spacecraft diagram turn to the horizontal position, I would give a fist pump!” he said. “I felt that success is almost certain!”

The G-Plot switched to show “Moon Landing Mode” but the attitude of the pictorial SLIM was not horizontal. Like Mori’s model landing earlier than night, SLIM’s attitude appeared to be vertical.

Looking at the G-Plot from the English broadcast room, I did not immediately realise that there was an issue. I assumed that the attitude had simply not reproduced correctly now that SLIM was on the ground. Mori also thought this might have been the case.

“I thought there was a good chance that the landing had been successful,” he said. “The calculation of the attitude is complex, and it’s common for the calculations to fail if the attitude extends past a certain range.”

But if everything had gone according to plan, we would have expected to hear the cheer from the mission control room just a few doors away.

We waited. But there was silence.

Situation: unknown

January 20 at 00:20 am: On the Moon

Standing in the middle of the mission control room, Miyazawa Yu had noticed two facts. The first was that SLIM’s attitude was not the expected orientation. The second was that the solar cells were not generating power.

Miyazawa was the control room supervisor that night. Her job was to receive reports from each of the spacecraft subsystem supervisors, and direct the commands that would be sent to SLIM. It was an intense role that rotated between the team members to allow major operations to continue around the clock.

“Everything went amazingly perfectly until just before landing,” Miyazawa recalled. “But although this was unexpected, we had prepared a procedure for the case where the solar cells were not generating power.”

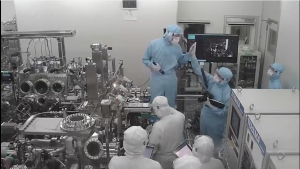

Inside the control room during SLIM’s descent and landing.

Without the ability to generate power, SLIM had to rely on its battery. This had a lifetime of only a few hours. Even though the origin of the problem was not yet known, the next steps were clear; all data from the landing had to be downloaded to Earth before the battery ran out and SLIM became unreachable.

“Since SLIM was working perfectly until just before landing, I was able to confirm that there was sufficient battery power remaining and we had enough time to retrieve all the necessary data,” Miyazawa said. “So although I was a little shaken, I did not panic.”

The downloading data also highlighted another important fact; SLIM was operational on the lunar surface. Japan had therefore successfully made a soft-landing on the Moon.

Situation: off-nominal.

January 20 at 00:30 am

While the SLIM team focussed on the spacecraft, an emergency consultation was taking place elsewhere on the campus. With the exact situation of the spacecraft still unknown, when was the right time to start the press conference?

Journalists had gathered in Communication Hall for 00:30am, but were expecting a potential delay of several hours to allow examination of data from the spacecraft.

As more information on the spacecraft status arrived on Earth, the SLIM team began to suspect the reason for the lack of power generation was that SLIM’s solar panels were not facing the Sun. The spacecraft did indeed seem to have landed in an unexpected orientation, with the main engine pointed upwards. But how this had occurred, and whether SLIM had definitely achieved pinpoint accuracy in reaching the target site remained unknown.

Outside the mission control room and in front of the cameras, Toriumi could only ask people to repeatedly wait for news.

“It was stressful to have to repeat the same announcement,” admitted Toriumi. “But our mission was only to convey the facts, we couldn’t make a judgement of the situation on our own.”

Like the mission control room, a decision regarding the live broadcast in the event of an off-nominal situation had been made in advance. At 00:30am the cameras were cut. Toriumi made a final announcement that the broadcast would start again with the press conference.

“It was only about ten minutes from the lunar landing to stopping the stream,” said Murakami. “But it felt so long.”

In the emergency consultation room, a decision had been made to start the press conference at 02:10am.

“We were stuck between not feeling able to keep the reporters waiting any longer, but also wondering what on Earth we were supposed to say,” said Fujimoto. “Had we waited another two hours and then held the press conference, the content would have been nice. But this was not considered to be an option. I wonder if that was really true.”

January 20 at 02:00 am

In the mission control room, the SLIM team had switched to an unexpected task. While SLIM was primarily a technology mission to demonstrate the pinpoint landing technique, the spacecraft did carry one scientific instrument: a multi-band spectroscopic camera that could examine the mineral composition of the nearby rocks by observing the reflected light at different wavelengths.

In the planned procedure for the situation where the solar cells had not been able to generate power, the downloading of the spacecraft data would be the highest priority while battery power remained. The multi-band camera would therefore not be used. However, the data was now all safely on Earth and the battery was not yet flat.

A command was issued from the mission control room. On the Moon’s surface, the multi-band camera onboard SLIM flicked into life and started to send back images.

“This was a relief!” said SLIM Project Scientist Sawai Shujiro. “We could confirm the multi-band camera was working normally.”

Moreover, the strange posture of SLIM offered a glimmer of hope. The team were relatively sure that the solar cells were facing west. This meant that there was no incident sunlight during the current lunar dawn, but this would change once dusk approached. It was therefore possible that power would be restored to SLIM at the end of the lunar day, in about 1 – 2 weeks.

However, the day would be dangerous. With no atmosphere to dissipate heat, temperatures at midday on the Moon surface could rise above 120°C and cause SLIM’s onboard instruments to exceed safe operating conditions. SLIM might therefore cook before it could wake up.

As SLIM’s battery dropped to 12%, Miyazawa sent the command to disconnect the power. It was a threshold that had been decided in advance. If the battery charge became too low, then it might not be possible to revive even if SLIM survived the lunar day.

The multi-band camera had photographed a large fraction of its field of view, but had not tested the operation of the filter wheel, which allowed images to be captured at different wavelengths. While Sawai had concerns about this, he knew it was the right decision to stop.

“We heard from the multi-band camera science team that they were confident about the operation of the filter wheel,” Sawai said. “And considering the complexion of the person in charge of the power supply, we decided not to carry out that check.”

At 02:57am, SLIM went to sleep.

January 25 – 28

Mori was being laughed at by his family.

Despite the emergency situation, SLIM had successfully released two small Lunar Excursion Vehicles, LEV-1 and LEV-2 just before reaching the lunar surface. LEV-2 (also known as SORA-Q) was a tiny ball-shaped rover that popped open create wheels and reveal a camera. It had rolled around on the Moon and taken a photograph of the SLIM spacecraft, sending it back to Earth via the antenna on LEV-1. The photograph confirmed that the attitude shown on the G-Plot had been completely accurate. SLIM had gently landed head-down in the lunar regolith.

“The G-Plot was scarily accurate,” said Mori in awe.

Based on the data the SLIM team had downloaded on the night of the landing, the spacecraft attitude shown in the LEV-2 photograph was now expected. But when Sakai saw the image, he went weak at the knees.

“It was the first time in more than 20 years of working in the field that I had actually seen something we had created in space,” he said. “I was overwhelmed.”

SLIM’s posture was also surprisingly close to the orientation in which Mori had accidentally landed the SLIM model during the live broadcast, as the spacecraft stood vertically, albeit upside down.

“That’s a perfect flag collection,” chuckled Mori’s sister on the family LINE account, an expression in Japanese pop culture to mean the story ended as expected.

“You predicted it!” agreed Mori’s brother.

While initially dismayed that he might have foreshadowed SLIM’s unexpected attitude, Mori was now reconsidering. SLIM uses lightweight thin-film solar cell sheets instead of conventional solar cells. Although the angle of sunlight was the most likely reason for the lack of power, a fault with the new thin-film design could not be completely ruled out. If SLIM had landed with its solar cells facing the lunar surface, then electricity generation would have been impossible, and the performance of the solar cell sheets would remain uncertain. However, the spacecraft’s perpendicular stand on the Moon should still allow for sunlight to hit the solar cells once the lunar dusk fell. Mori was keen for a chance to prove this technology.

“I consider thin-film solar sheets could be essential for future deep-space exploration,” explained Mori.

As lunar dusk fell and the sun moved across the Moon’s surface, the SLIM team continued to send communications to the spacecraft.

And then, eight days after landing, SLIM answered.

January 28 – 31: back in business

The multi-band spectroscopic camera team were busy naming Moon rocks after dogs. Cats had been considered, but the range of sizes in the images being returned from the lunar surface were better suited to different dog breeds. From a scientific perspective, SLIM’s unusual headstand posture was proving to be a huge success.

“With SLIM’s design, the current attitude is almost the best attitude for scientific observations!” said Sawai.

The spacecraft vertical headstand might not have looked optimal, but the resulting field of view for the multi-band camera was excellent, encompassing a full dog pack of rocks that the team wanted to observe.

The planned orientation for SLIM would have placed the solar cells facing east, allowing SLIM to operate during the lunar dawn before temperatures rose and degraded the observations with thermal noise. As the Sun rose in the lunar sky, SLIM would also have been able to view the surface in a range of lighting conditions.

However, an equally good time was dusk, which had been made possible by the now west-facing solar cells. The delay while the team waited for the Sun to set had also been beneficial, as there had been time to consider the operational plan based on the first glimpse of the Moon surface after landing. The risk had been survival through the lunar day, which might have damaged the spacecraft or camera. But luck had been on our side, and the SLIM science program was back in business.

Exactly what had happened during the last 50m descent is still under investigation. Data downloaded from SLIM show that the spacecraft suddenly lost the use of one of the two main engines. Images show what appears to be a nozzle falling away from the spacecraft. What caused the damage is still not clear. But despite such a major incident, SLIM was able to use the single remaining engine to complete the soft-landing. The off-centre thrust from using only one engine caused the change in attitude.

The data also revealed that the pinpoint landing technique had been a perfect success. SLIM had touched down 55m from the target landing site, well within the 100m goal for the mission. Moreover, SLIM had been between 3 – 10m of the landing site before the final 50m descent. Past this point, SLIM was expected to move off-course as it autonomously adjusted its position to avoid hazardous boulders. Obstacle avoidance plus a drift from the off-centre main engine pushed SLIM to the east.

“I honestly feel glad that we were able to land under these conditions,” said Sakai. “I feel like I should be grateful to someone or something, especially given that the attitude after landing was very convenient for observations with the spectroscopic camera.”

The loss of one of the main engines did mean that SLIM was not able to demonstrate the two-step landing. Sawai does feel regret that it was not possible to achieve a perfect success for the junior SLIM team members. However, he hoped that SLIM has also demonstrated an important lesson about space exploration.

“Even if you do everything you can think of and persist in performing checks, success is still not guaranteed!” he said. “Therefore, you can never cut corners.”

As night fell on the lunar surface at the end of January, SLIM once again went to sleep. As with the middle of the day, temperatures during lunar night are extreme, with drops below -170°C making survival difficult. The mission had not been expected to continue past dark. But to the delight of the team, SLIM did wake as the Sun rose and moved across the sky to once again illuminate the spacecraft’s solar panels. However, later tests of the multi-band camera were not successful, suggesting that the rolling temperature extremes have finally taken their toll.

“Ultimately, we were able to demonstrate most of what we wanted to demonstrate,“ said Sakai. “And in particular, the pinpoint landing performance met our expectation, so I think this can be considered a success.”

After experiencing the extreme conditions of multiple lunar days and nights, and potential damage received from a strong solar flare, the team announced at the end of June that it was unlikely that communication could be established again with the little lander. SLIM had operated for many months on the Moon, far beyond the nominal operation plan.

The next steps

“Shioli” in Japanese means “bookmark”, reflecting the hope that SLIM’s landing near the Shioli crater will be a bookmark in the pages of history.

The pinpoint landing technique opens the door to a new era of exploration, where spacecraft can touchdown at precise locations. As humans once again head for the Moon with the international Artemis program, precision landing could allow investigation of potential resources, or deliver supplies to a future human base.

The success of the LEV rovers also points to new possibilities for wide-scale exploration of a celestial body.

“Rather than attaching landing legs to a spacecraft, it would be possible to carry out a new style of exploration in which we carry something like 10 LEVs and drop them onto the surface one after another,” Sawai envisions.

At 3am on January 20, Fujimoto had answered the journalist’s question about the serious atmosphere of the press conference. “First and foremost, we just want to know what has happened,” he said. “We’re currently thinking… what does the spacecraft look like now? What is the current condition? Once we know, we can plan the next step. We’re always thinking about the next step, so this kind of situation is very tough for us!”

With SLIM’s report from the lunar surface finally submitted, and the team looking towards new challenges, it perhaps finally time to smile.

Further information:

Cosmos: 20 minutes of terror: SLIM will attempt a pinpoint accurate landing on the lunar surface

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post