ISAS’s O’Donoghue is awarded the 2021 Europlanet Prize for Public Engagement

ISAS fellow Dr James O’Donoghue has been awarded the 2021 Europlanet Prize for Public Engagement! O’Donoghue describes his work in bringing scientific ideas to life in animation, and how the US Government shutdown kick-started his interest.

“I expected maybe dozens of likes and views, but the animation got 1.6 million views in two days on Twitter,” explains Dr James O’Donoghue, Department of Solar System Sciences. “I began to learn that I could make something in several hours that could sometimes be seen by millions of people within days. With only about 10,000 astronomers in our world of nearly 8 billion people, animated outreach is a nice way to fill the gaps for those who just cannot live conveniently close to attend talks at a university or research institutes.”

O’Donoghue is an expert in the gas giants of our Solar System, but it is not this work that is the focus of his latest acclaim. Alongside his research, O’Donoghue has created over 100 short animations that illustrate different scientific ideas. He shares these bite-sized movies on his personal twitter feed, and from there they have found their way into publications such as the New York Times, Business Insider, the Daily Mail and Futurism. The diverse readership of these sites demonstrates the universal appeal of O’Donoghue’s creations. It is a feat that landed O’Donoghue this year’s Europlanet Prize for Public Engagement, which is awarded for developing innovative and socially impactful practices in planetary science communication and education.

“The purpose of these animations is to convey a large amount of information about a scientific concept in a very short time, in a hopefully entertaining and unique way!” O’Donoghue explains. “I try to fill important gaps in people’s general knowledge, from children to adults, by providing visual demonstrations that are difficult to forget.”

O’Donoghue says he had noticed that many key facts about the Earth and Solar System were either taught too briefly and swiftly forgotten, or not taught at all. He cites one example as the time for the Earth to rotate, which is usually considered to be 24 hours but is more exactly 23 hours and 56 minutes.

“It seems to be a half-known thing,” says O’Donoghue. “And those that do know it often think that is the reason we have leap years, but that is not so!”

The leap year is due to the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, not the planet’s own rotation. It takes almost 365.25 days to circle the Sun, but this is rounded to 365 days for convenience. Every four years we therefore add one exact “leap day” to the year to catch up with the Earth’s actual orbit. O’Donoghue created different animations to show both the rotation of the Earth and why we need a leap year.

“I even made a video showing what happens if you don’t add leap days,” chuckles O’Donoghue. “The short answer is that the seasons drift!”

Each animation typically lasts less than a minute, proving how visual information can often be shared extremely efficiently, compared to several paragraphs of text. O’Donoghue notes that recognising the power of animations can greatly help scientists share their work.

“Animations have demonstrably drawn larger crowds to regular news on new scientific results,” O’Donoghue points out. “An article or press release on a new discovery might get visited 1,000 times ordinarily, but this can be multiplied by 10 or 100 if exciting graphics and/or videos are involved.”

Leveraging on the popularity of graphics and animations can explode the efficiency of public relations teams, as O’Donoghue has noticed that an available animation typically results in many more news articles covering the topic. Part of the reason for this is that animations engage with a much wider audience and especially with younger people, and this also helps to inspire the next generation of scientists and engineers.

“Even videos I’ve made that are not related to recent scientific discoveries have received hundreds of news articles,” says O’Donoghue. “This really highlights that science when communicated visually is highly interesting to people.”

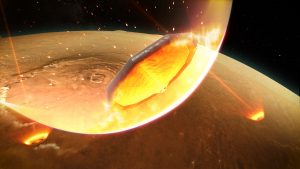

O’Donoghue created his first scientific animation to demonstrate an unusual scientific finding in his own work. He had discovered that the rings of Saturn were falling onto the planet in a phenomenon dubbed “ring rain”. The research and animation was published in the New York Times on December 17, 2018. Just a few days later, a US Government shut-down began that was to last 35 days. Based at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center at the time, O’Donoghue found himself with unexpected time to spare.

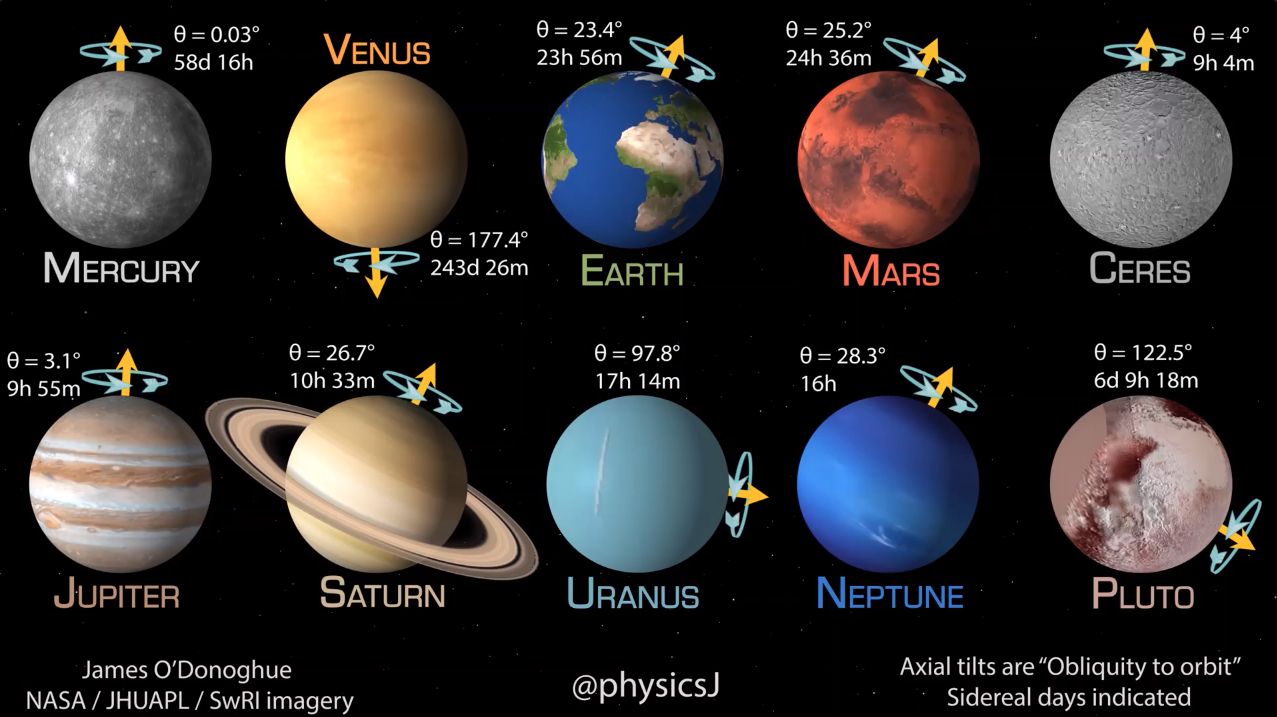

“We were told not to work, not even check our emails!” O’Donoghue recalls. “At a loose end, I made an animation showing the eight planets rotating at their correct relative speeds and with their tilts being accurate, which I had determined did not yet exist.”

This was the animation that received 1.6 million views in two days after O’Donoghue posted it on twitter. As the shutdown continued and people on twitter clamoured for more, O’Donoghue continued to create and had his next “hit” with an animation showing how fast the speed of light is in comparison to distances within the Solar System. It was something he had wanted to demonstrate for many years.

“The topics I chose are sometimes based on frequently asked questions, like why we need leap years,” O’Donoghue explains. “Some I made just because I really wanted to see what they would look like, such as what the Moon would look like in the ancient past when it was closer to the Earth.”

To make these animations, O’Donoghue uses Adobe After Effects. He selected that program due to his familiarity with other Adobe products, which helped to become comfortable with the interface. He proceeded to teach himself the package through videos, blogs and forum posts where he found the answers to most of his questions. However, he does note that this was not the most efficient way to build his skills.

“For the first 50 or so animations I made, each new video usually involved learning something new,” O’Donoghue explains. “If I were to give tips to a budding animator, it would be to do at least some simple online course for the program you use. I think my approach of going into the deep end worked in the end, but I probably wasted a lot of time not knowing certain key things up front!”

That said, O’Donoghue does say he enjoyed hunting out a solution and the exploration through the online information helped to learn different techniques that he would later employ in subsequent videos.

“It’s mainly important that you enjoy what you’re doing, first and foremost!” he concludes.

On receiving the Europlanet Prize, O’Donoghue thanks everyone who has offered kind words and thought provoking questions in response to his animations, as well as the educators who have written to say they have used the animations for teaching in schools through to planetariums! He also extends a personal thank you to his wife, Jordyn, for her endless patience over the years. O’Donoghue plans to continue to create animations as part of his work as a researcher. The recognition brought by the award from the Europlanet Society he hopes demonstrates the value outreach can bring to large scientific organisations.

“I believe outreach is an integral part of science in society and that we have a duty to make it accessible for all the people who fund it and to share the work going on at the frontier of science,” says O’Donoghue. “I aim to reach everyone I can around the world at any age, free from assumptions about their prior knowledge.”

Further information:

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post