We’re going to the Martian moons!

ISAS@JAXA is excited to announce a new mission to Mars to explore the red planet’s two moons and bring back a sample of moon material to Earth.

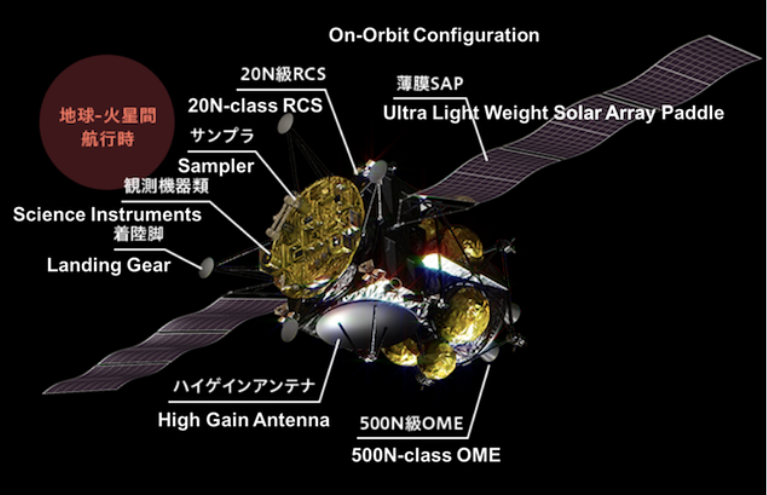

The Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) mission is scheduled to launch from the Tanegashima Space Center in September 2024. The spacecraft will arrive at Mars in August 2025 and spend the next three years exploring the two moons and the environment around Mars. During this time, the MMX spacecraft will drop to the surface of one of the moons and collect a sample to bring back to Earth. Probe and sample should return to Earth in the summer of 2029.

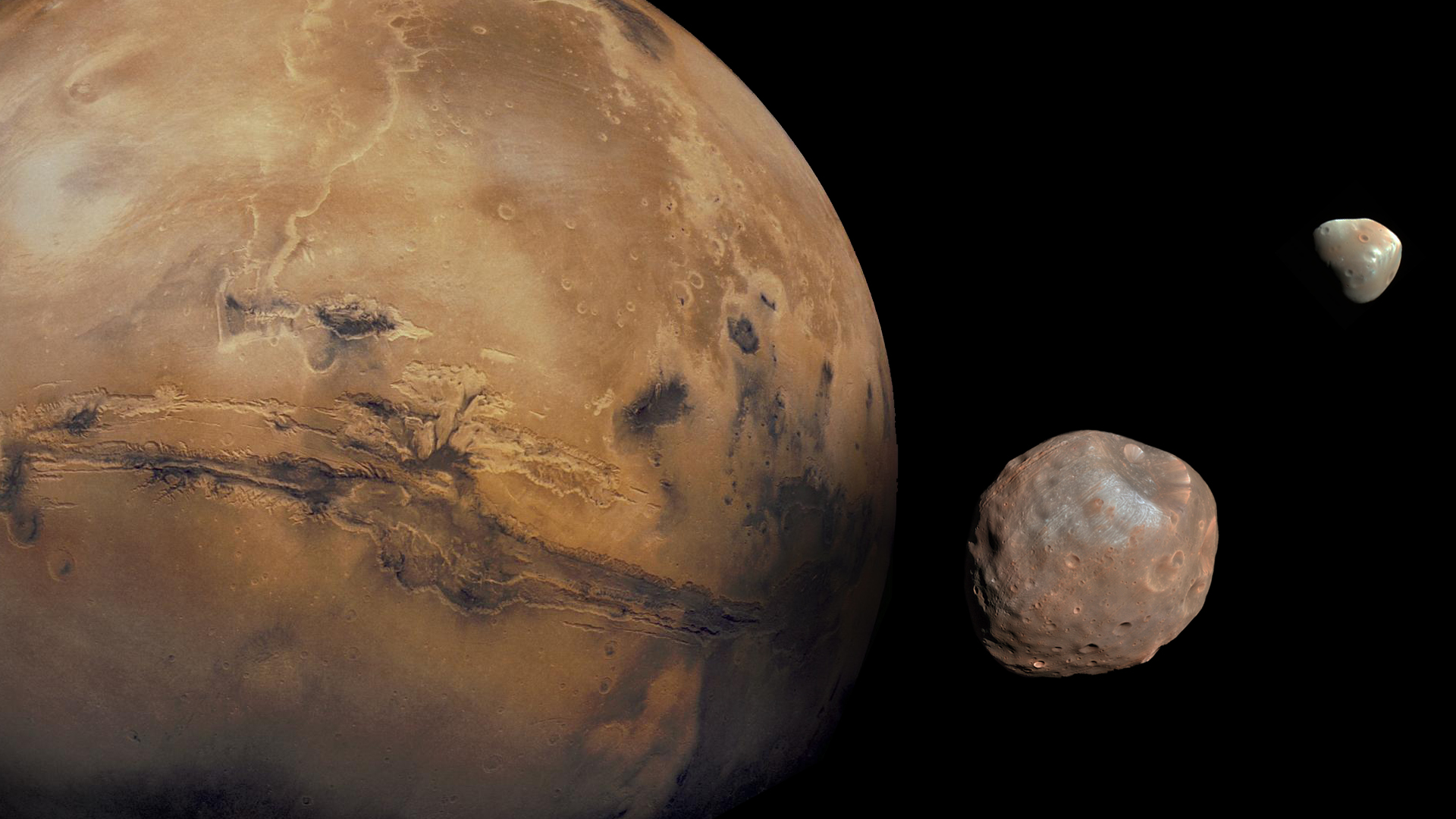

Mars takes its name from the god of war in ancient Greek and Roman mythology. The Greek god ‘Ares’ became ‘Mars’ in the Roman adaptation of the deities. Mars’s two moons are named for Phobos and Deimos; the twin sons of Ares who personified fear and panic. In reality, the moons really personify a mystery regarding their formation.

Both Martian moons are small, with Phobos’s average diameter measuring 22.2km, while the even smaller Deimos has an average size of just 13km. This makes even Phobos’s surface area only comparable to that of Tokyo. Their diminutive proportions means that the moons resemble asteroids, with irregular structures due to their gravity being too weak to pull them into spheres.

This leads to a key question: Were Phobos and Deimos formed during an impact with Mars, or are they asteroids that have been captured by Mars’s gravity?

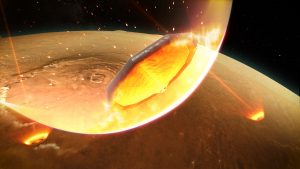

Our own Moon is thought to have been created when a Mars-sized body slammed into the early Earth. Debris from the collision was thrown into the Earth’s orbit where is coalesced into our only natural satellite.

A similar scenario is possible for Phobos and Deimos. In the late stages of our Solar System’s formation, giant impacts such as the one that struck the Earth were relatively common. Mars shows possible evidence for one such collision with a body the size of our Moon. The Martian surface has a dichotomy consistent with such an event, with the northern hemisphere sitting an average of 5.5km lower than the southern side. During such impacts, debris could have been thrown up from the Martian surface to birth the two moons.

An alternative scenario is that the resemblance of Phobos and Deimos to asteroids is not coincidental. The two moons may have originally been part of the asteroid belt; a band of rocky left-overs from the planet formation process that circle the Sun between Mars and Jupiter. Scattered inwards towards the Sun during a chance collision, the asteroids may have been snagged into orbit by Mars’s gravity. Observations of both moons suggest that their surface material is similar to that of other asteroids.

Disentangling these two possible births is the primary goal for the MMX mission. If the moons were formed from the body of Mars itself, their rock type should resemble that of Mars. On the other hand, if the pair were captured then they would have formed in a different part of the Solar System with their own distinct composition.

Both options would reveal a great deal about the formation of our Solar System. The young Mars is suspected to have been similar to the early Earth. If Phobos and Deimos formed during this time, the moons could be preserved time capsules of what conditions were like on the planets in this epoch. This would help us understand the formation of the Earth and maybe even the development of habitability.

On the other hand, the Earth’s water is suspected to have been delivered to our planet after its formation by impacts from icy meteorites. This water delivery service may have originated in the asteroid belt (one rocky member of which is currently the destination of JAXA’s Hayabusa2). If Phobos and Deimos are captured asteroids, they may be kin to the ice-packed rocks that hit the early Earth, revealing information about how volatiles were circulated about our Solar System.

The Martian Moons eXploration spacecraft is planning to study both moons and collect rock samples from one of the two small satellites. Phobos’s orbit takes it closer to Mars than Deimos, circling the planet at about 6,000km above the surface. For comparison, the Moon is 385,000km above the Earth. One of the exciting advantages of this target is that Phobos’s close proximity means that the moon’s surface should have a loose layer of regolith or soil sprayed up from Mars during more recent impacts with meteorites. Samples taken from Phobos are therefore expected to contain Martian meteorites and the moon’s own material from deeper down. This extra Martian regolith may be very different from the rocks that make it to Earth. The shorter journey to the close-by moon allows the transfer of lower density material that would never survive the trip to Earth. The regolith will also originate from all over the planet, rather than the small region of Mars that has been explored by landed rovers, providing a more wide spread sample than has previously been analysed.

This will be JAXA’s third mission to sample material from a small body. Hayabusa visited the asteroid Itokawa, bringing back surface material to Earth from the asteroid in 2010. Its successor, Hayabusa2, is currently travelling to asteroid Ryugu and is expected to arrive in 2018. With only 1/1000th of the gravity on Earth, landing on Phobos is a challenging task. However, the risks are worth taking for the knowledge a sample return mission can bring.

Updates for the Martian Mission eXploration mission can be found on the mission webpage in English and Japanese. Will you rooting for #TeamImpact or #TeamCapture?

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post